Karen Strassler

Karen Strassler is a cultural anthropologist at Queens College in New York whose research focuses on photography and the media, specifically looking at the social lives and political work of images. Her work explores the relationship between visuality and political imaginaries while addressing the profound changes in Indonesian culture over the last 30 years. Her first book, Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java (Duke University Press, 2010), addressed the role of photography in shaping social and political culture in the time of Suharto. Strassler’s most recent book, Demanding Images: Democracy, Mediation, and the Image-Event in Indonesia (Duke University Press, 2020, addresses similar issues as the country experiments with democracy while confronting the mass media in the 21st century. Here Karen speaks with photographer Brian Arnold about her work and interests in Indonesia, photography, image culture, and politics.

Can you tell us something about your first exposure to Indonesia? What was it that first affected your imagination? And how has this changed over the years?

My first exposure to Indonesia was as a young child, in the home of relatives who had lived and worked there in the late 1960s to early 1970s. Their apartment was decorated with richly patterned textiles, puppets, and wood carvings, objects that fascinated me because they were both beautiful and strange. I first traveled to Indonesia as a college student in the late 1980s. I was studying about nationalism, feminism, postcolonialism, and development in the so-called “Third World.” When I found out there was a semester abroad program in Bali, I saw a chance to combine my current interests with my childhood fascination. I had a fantastic time and was blown away by the richness of Balinese arts. I learned the basics of Indonesian, caught a glimpse of what it was to live in an authoritarian regime. A couple of years later I spent some time traveling in Java and Sumatra, but I didn’t imagine Indonesia would play a big part in my future. Then in the mid-1990s I found myself enrolling in a PhD program in Anthropology at the University of Michigan, which happened to have an excellent Southeast Asian Studies program and brilliant faculty (Ann Laura Stoler, Rudolf Mrazek, Nancy Florida, and later, Webb Keane) who specialized in Indonesia. When Ann Stoler offered me a job as a research assistant for an oral history project she was starting in Java, I got my first real taste of fieldwork—and I was hooked. I found interviewing people, straining to understand and gain access to the worlds they described, intensely exciting. I also took pleasure in the more mundane aspects of the research process: wandering back alleys, buying snacks from food carts, watching kids play in dusty empty lots, and striking up random little conversations as I searched for former servants who had worked in Dutch homes in the final years of the colonial era. By this time, I was getting interested in political violence, authoritarianism, and memory. I was also delving into the rich body of anthropological work on Java and other parts of the archipelago. For numerous reasons, but perhaps particularly its history of authoritarian rule and mass violence, Indonesia was a really fascinating place to think through questions I had about politics, historical memory, and, of course, the work of images. But a core sensuous attachment to the smells, sights, and sounds of the place and a passion for engaging with people—many of whom I have found exceptionally funny, insightful, smart, and creative—runs deeper than any academic engagement I have with Indonesia.

Cover for Refracted Visions

How did you get interested in photography and vernacular visual culture?

I came to graduate school in the mid-1990s interested in media technologies and their impact on and relation to culture. I was new to anthropology and found it shocking that (at the time) anthropology had such rich tools for investigating language and discourse but was relatively impoverished and, in fact, quite dismissive when it came to approaching the visual. Visual Anthropology was a marginalized subfield that mostly focused on anthropologists making ethnographic films rather than looking at the visual practices and images of the people we study. I felt strongly that there was no way to understand our contemporary world without a better set of tools for understanding how people live with and through images. This concern with the everyday, ordinary ways that people and images make each other led me to look at vernacular visual photography. At a time when many anthropologists were starting to write about mass media like television and film, I felt and still feel that the camera is an extraordinary tool that allows people to not just passively receive images but to make them and use them for their own purposes. These ordinary forms of self-documentation, often dismissed as banal and formulaic, can be quite revealing if we take images seriously as social mediators and artifacts of the imagination, and if we attend closely to what people actually do with and say about them.

I was very lucky that in my first year of graduate school, I took a seminar on modern Indonesian history with the historian Rudolf Mrazek. I was looking for a topic for a seminar paper and I stumbled upon a complete collection of a late colonial magazine (Netherlands East Indies Old and New) that was housed in the University of Michigan library. It was full of wonderful photographs of the colony, some of them taken by amateurs. I wanted to write a paper analyzing how the images represented the Netherlands East Indies and how the colonial picture changed over time. But I questioned whether, not being able to read Dutch, I could legitimately write a paper about the magazine. Rudolf told me to go ahead and do the visual analysis. He wasn’t saying that ultimately the text was unimportant, but he was giving me permission to explore and develop my ability to work with images. He helped me free myself from the textual bias that makes us always anchor and guide our readings of images according to captions and other text. This is why I insisted on a design for Demanding Images that placed captions at the bottom of the page rather than immediately under or next to the image. I want to interrupt that too-easy move to text as that which explains the image. I want to teach us, as anthropologists, to reverse our default assumption that images illustrate, and are therefore subordinate to, text.

Do you have any formal education or background in photography or the visual arts? Do you use a camera yourself as part of your research collection process?

I am a very visual person, and I enjoy taking pictures, but I have never considered myself to be an accomplished photographer or anything other than an amateur artist. I took an analogue photography class in high school and so have basic understanding of how to use a camera and how to develop film. In college, I also did some photography and took several art classes. I continue to paint in my free time. When doing the research for my first book, people often assumed that I was very knowledgeable about photography. Sometimes amateur photographers would talk to me at great length and in highly technical terms about lenses and other equipment, and I really had no idea of what they were talking about. I was interested in the social and aesthetic aspects of photography rather than questions of technique. But the camera was and is indispensable to my research process. In the research for my first book, which was conducted in 1998-2000, I used an analogue Nikon camera, even though digital cameras were already available (but expensive for a graduate student!). I used it to document other people taking and using photographs and to create an archive of people’s personal photographs. To make reproductions of albums and photographs, I just used a tripod and a neutral grey piece of foamboard. It was unprofessional, but it worked. For my second book, I relied entirely on my iphone camera to document images that I observed in the streets and other public settings. I collected a lot of ephemera (like campaign stickers and tabloids) and I also relied on downloading images from the internet. The quality was not as good, but this seemed fitting for a book that was largely about what Hito Steyerl calls “poor images.” So, my own use of photographic technology, from 35 mm film camera to cell phone, mirrored the changing photographic worlds I was documenting in each book. Refracted Visions traced the largely paper-based, analogue world of photography from the mid 19th through 20th century, and Demanding Images explores the digital image-world and media ecology of the early years of the 21st.

Cover for Demanding Images

Reading your texts, you often site cultural and literary philosophers like Ben Anderson or Mikhail Bakhtin. Are there philosophers of visual culture you find important for developing your own conceptual framework? John Berger or David Levi Strauss, for instance?

I think Roland Barthes and Walter Benjamin most profoundly shaped my thinking about photography. I’ve had something of a love-hate relationship with Barthes’ Camera Lucida over my many years of reading and re-reading it, but whether it provokes me or moves me to tears, it has been a profoundly generative text to think with and against. Benjamin offers so many essential insights: about how reproduction allows images to meet people “in their own situations,” about the optical unconscious and the contingency of the photograph, about the disruptive potential of images from the past, about how photography transforms social life and even the human sensorium. Methodologically, his Arcades Project remains inspirational to me. There are few books I enjoy teaching as much as John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, an indispensable classic. Many other visual theorists have been foundational for me: Kaja Silverman, WJT Mitchell, Alan Sekula, bell hooks, to name a few more. I would say that I’m deeply engaged with visual theory, but I am also eclectic in my approach: I will use anything that seems helpful for understanding the phenomena at hand. Barthes’ essays on photography and film in Image-Music-Text were important early influences on my thinking, but no less so were his essays “Death of the Author” and “From Work to Text.” Bakhtin’s notion of refraction, as well as his approach to genre, just worked for what I wanted to say about photography in Refracted Visions. I don’t see any reason to limit myself to visual theory.

You were in Indonesia in the late 1990s for reformasi, and in the United States for the Trump era. Can you say something about the role of photography in democracy?

To state it maybe too boldly, in our current image-saturated media environment all politics has become image-politics. Gaining and maintaining political power is largely a matter of controlling the field of vision, of shaping what is seen and how it is seen. But managing the visual field has become increasingly difficult; new technologies for making and circulating images and new platforms for their dissemination render the realm of appearances increasingly unstable and unruly. The camera has always been used as both an instrument of power and as a means for challenging power whether directly, by exposing wrong-doing, or more subtly by shifting the ways that we see and opening up new domains to the field of vision. What has changed is that today more people have access to cameras and more people can operate as what anthropologist Zeynep Gursel calls “image brokers,” playing a role in making, selecting, circulating, and altering images. This is why, as I argue in Demanding Images, the “image-event” is an increasingly important political process in democratic societies. While an earlier generation of scholars theorized the growing role of images in politics in terms of the spectacle, the concept of the image-event is about engagement: it is about acts of making, altering, scrutinizing, and commenting on images as a form of political praxis and citizenship. I’m not naïvely suggesting that giving people cameras is inherently empowering nor that images always live up to our dreams for them, doing the political work we want them to do. I’m not suggesting that clicking on an image or posting on social media leads to or safeguards democracy. More often than not, images fail us—or we fail them. Of course, states (and corporations) have enormous power to shut things down, to censor and destroy, on the one hand, and to flood the image-scape with their own preferred visions, on the other. Responding to images can be a form of action that takes the place of other kinds of potentially more consequential political acts. Images and their environments are also changing, as are the political worlds in which they intervene. Journalistic images no longer occupy the same privileged position to tell truths, they now compete with other image-forms like memes that make their claims through different media platforms and different rhetorical modalities. But my basic argument in the book is that images are dynamic, unfinished, and unfolding happenings in time and space. They are inherently unruly and their effects are unpredictable. That can gather and galvanize people. They can crystallize imaginings that have been inchoate or elusive, providing a material ground for debate and struggle. They have the potential to disrupt what has been taken as given and to transform the ways that we see. For these reasons, they are crucial to democratic politics.

Writing in the Rain (video still), FX Harsono, single channel video, 6’02”, 2011. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Australia and FX Harsono.

Do you follow contemporary art or photography in Indonesia? If so, has this shaped the fundamental questions of your work or approach?

I don’t follow it in a systematic way, but I am certainly very interested in contemporary art and art photography in Indonesia. I’ve recently been developing a project that has to do with ethnic Chinese, visuality, and histories of violence, and as part of that I’ve been writing about a body of work by the artist FX Harsono that addresses massacres of ethnic Chinese during the Indonesian revolution. I’ve been lucky to get to know Harsono and I find his art powerful and moving and extremely helpful for thinking about memory, silence, and the work of repair in the aftermath of violence. I’ve also had the opportunity to engage with the Australia-based Indonesian artist Tintin Wulia—I was invited by the Asian Art Archive in America to be in “conversation” with her about her fantastic video, “1001 Martian Nights,” last spring. There are several other artists whose work I’ve been loosely following in recent years. I am not an art critic, an art historian, or an anthropologist of art—I’m not doing a study of Indonesian art practices or markets or institutions. It’s a matter of thinking with contemporary artists, rather than about them. I’m using their works as guides, as beacons really, that light my way toward new insights about relations between the visual and history, memory, politics, materiality, and sensuous embodiment. I think of contemporary artists as visual theorists from whom I have a great deal to learn.

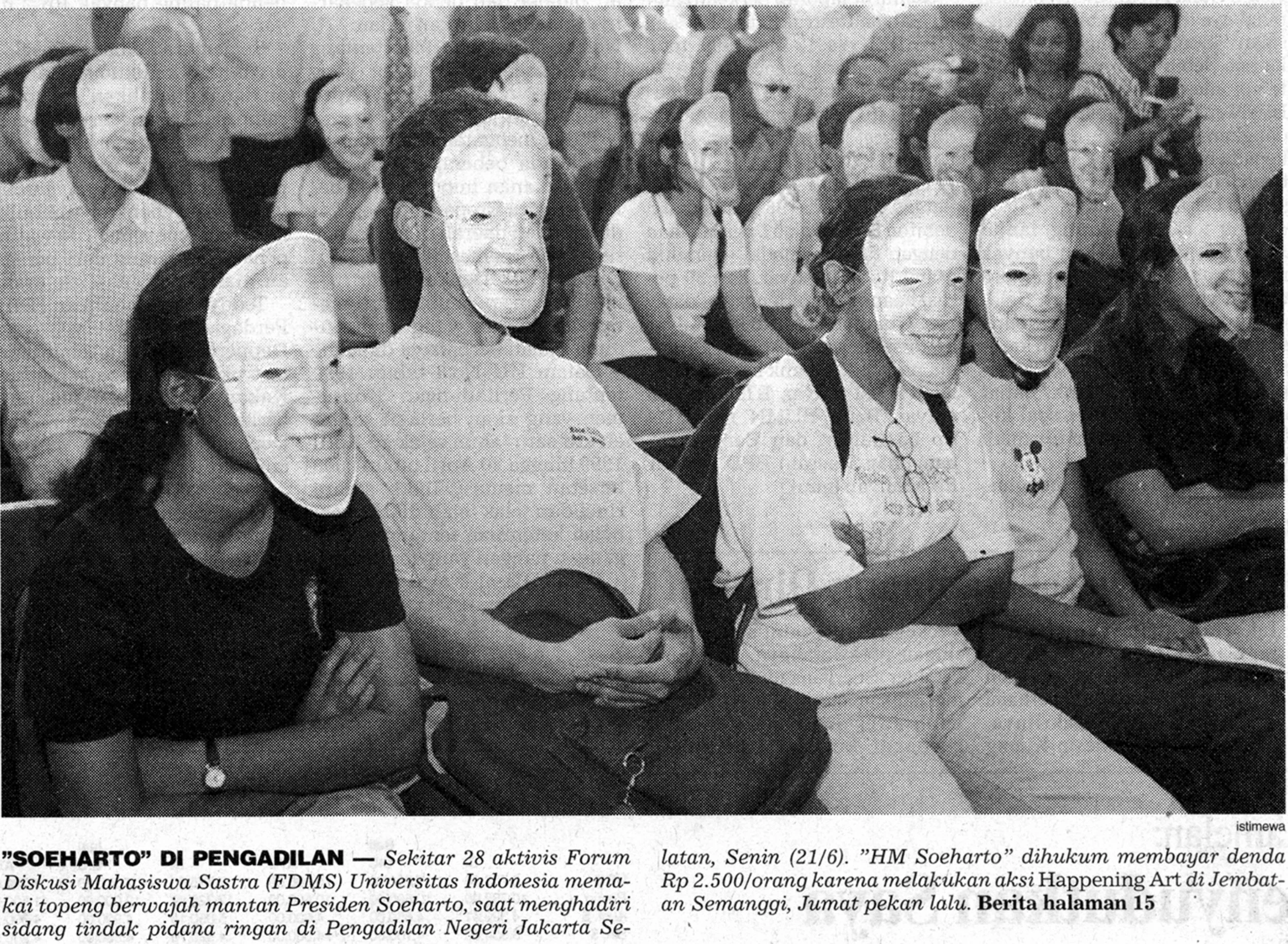

Students appear in court wearing Suharto masks. From “’HM Soeharto’ Dihukum Denda” (Suharto sentenced with a fine), Kompas, June 22, 1999. Courtesty of Karen Strassler and Duke University Press.

What are you working on today?

The project mentioned in my last answer is still very much in a preliminary phase, but it’s provisionally called “Seeing/Unseeing the ‘Chinese’ in Indonesia.” I am interested in thinking about ways that “Chineseness” as a racialized identity in Indonesia has been constructed and contested visually. I want to look historically at the visual processes by which a putatively distinct racial category of people was produced: whether through the production of images, colonial-era sumptuary laws governing how people dressed, the built environment and material culture, stereotypes of physical appearance, and so on. I also want to trace periods and forms of erasure and state-imposed blindness. The most obvious of these are the early New Order laws that compelled people to change their names and forbid the presence of Chinese language and signs of culture in public.Alongside the historical work, I plan to look ethnographically at the ways that “Chineseness” in Indonesiatodayis both visible and invisible, in often ambiguous and shifting ways, and how ethnic Chinese navigate their emplacement in the visual field through various ways of manipulating appearances, through strategic forms of camouflage or refusal, and through licensed displays of Chinese culture. I’m also interested in the interplay of visuality with other ways of knowing or sensing Chineseness. At a broader level it’s a project about the durability of colonial ways of seeing, about the relationship between concrete visual forms and broader social and political imaginaries