BYRON HAMZAH

Byron is a Malaysian documentary photographer based in Malaysia and the UK. After pursuing a Masters in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography at the University of the Arts, London, we had a chance to speak to him about his practice and his current work Alasig a collaborative photography zine between Hamzah and the stateless children of Semporna in Sabah, Malaysia.

What is your route into Photography?

I started photography by chance about 10 years ago. I had a small garden at the back of my house which I invested a lot of time and effort to make it beautiful. Proud of what I have achieved, I wanted to share this with my family which led to me buying my first camera. Overtime, my photographic pursuits went beyond just photographing my garden and I started taking my camera everywhere and was photographing my friends and family. I started to realise my potential and photography started to become an obsession. I also fell in love with analogue photography and began exploring photography as an art. I started learning about its history and my search for inspiration led me to discover the greats such as Dorothea Lang, Steve McCurry and Fan Ho.

Can you tell us more about the Masters in LCC what have you learnt? And what is the impact on your current practice?

With regards to the MA, I felt that I wanted to learn more beyond the confines of photography manuals and YouTube tutorials. I had a particular desire to appreciate photography at an academic level. Whilst the occasional photography social groups I belong to served as a good incubation space for my growth, I was searching for a more formal conversation and guidance in my pursuit. I was driven by the desire to learn and understand photography beyond the limits of a ‘hobby’ because I was at a point that it was no longer just an interest but it had progressed to become a true passion. The course was life changing as I was learning photography by delving into the theories and its role and implication to society. This made me appreciate it at a different level; I was viewing images in front of me in a more comprehensive and well-rounded manner. In addition, the many photographers that I discovered during the time became a constant source of inspiration. Most importantly, it exposed me to how photography and the experimental potential it has as a powerful tool of storytelling, something that I will not have been aware of by myself.

How did this work come about? What drove you to make this work? Tell us about the collaborative process and the students involvement.

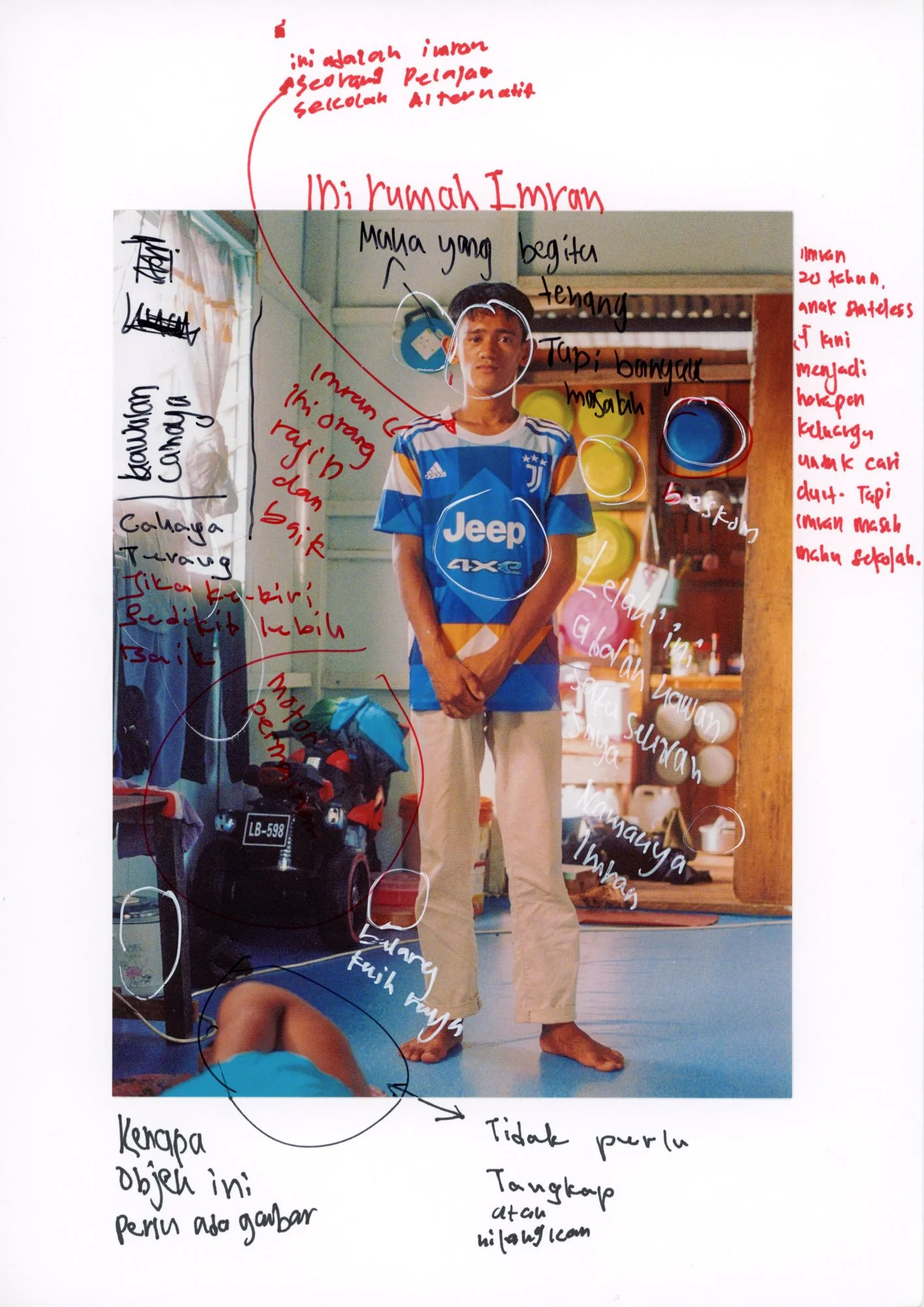

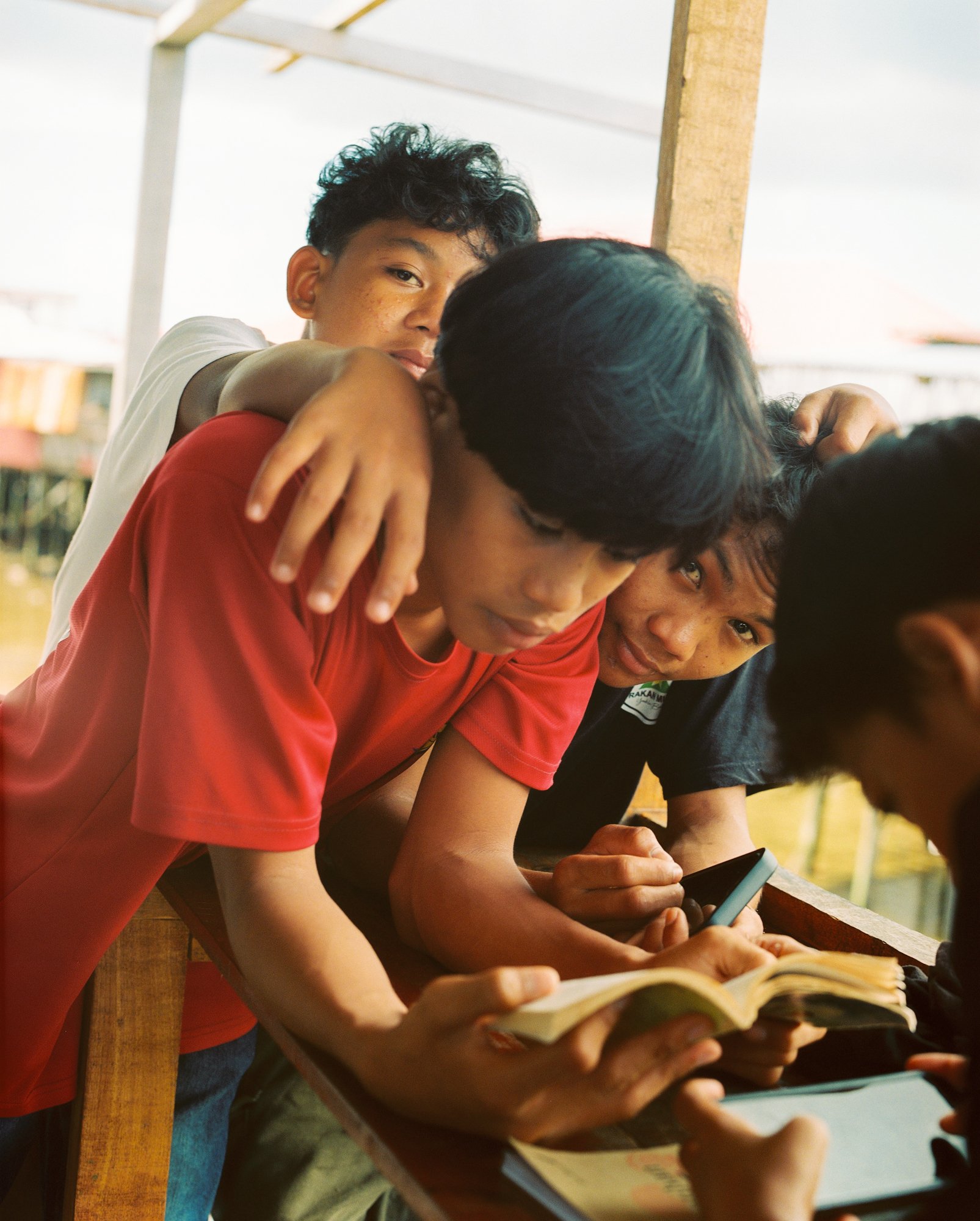

The issue of statelessness in Malaysia is a perennial and complex issue. I came to know about this via my mother a couple of years ago who has always been involved in some form of charity work. Whilst news on statelessness are mentioned every so often in Malaysian media, I’ve never really met a stateless person and only knew statelessness as an abstract concept. When I started speaking to individuals in this situation, it became more real and I wanted to learn more about it in real life. I also learnt about the complexity of this issue in East Malaysian states, which have the largest population of the stateless, complicated by the political and geographical element that makes this issue even more difficult to rectify in this region. My research led me to discover the NGO (Borneo Komrad) that I have been working with over the past two years. Since 2015, they have been instrumental in establishing several Alternative Schools that provide free education to stateless children around the East Malaysia state of Sabah. For the past two years, I have been working with them and collaborating with the children teaching art and photography. At the beginning, my work with the children was mainly confined to teaching and discussion about photography and art. Initially, I had no big aspirations of turning it into any major photographic endeavour and I did not have any specific long-term objectives for myself except to be at the school and take photos with the children. However, my work at the school also correlated with the time I was doing my Masters. Whilst I knew the documentary potential of my work, I was discouraged by the scope of the issue, the ethics and the logistics that would made it quite unappealing as a documentary project. Nevertheless, I also saw the potential and opportunity on how this work could lend a voice to the youths when such platform is needed. I felt that using the Masters would facilitate a more systematic approach to conceptualise such a complex topic whilst forcing me to reckon with the ethical considerations of representing those in crisis. I looked at many previous works by western photojournalists covering the issue of statelessness particularly in this region; whilst I believe that the works are relevant, it felt detached, sterile and at times, veered into poverty porn. The issue of statelessness, at least how it affects the youths, is beyond well-composed editorial imageries. I wanted the spirit and voice of the children to be present in the outcome of the work. I wanted to be the facilitator that reminds them of their own agency on how they can be represented.

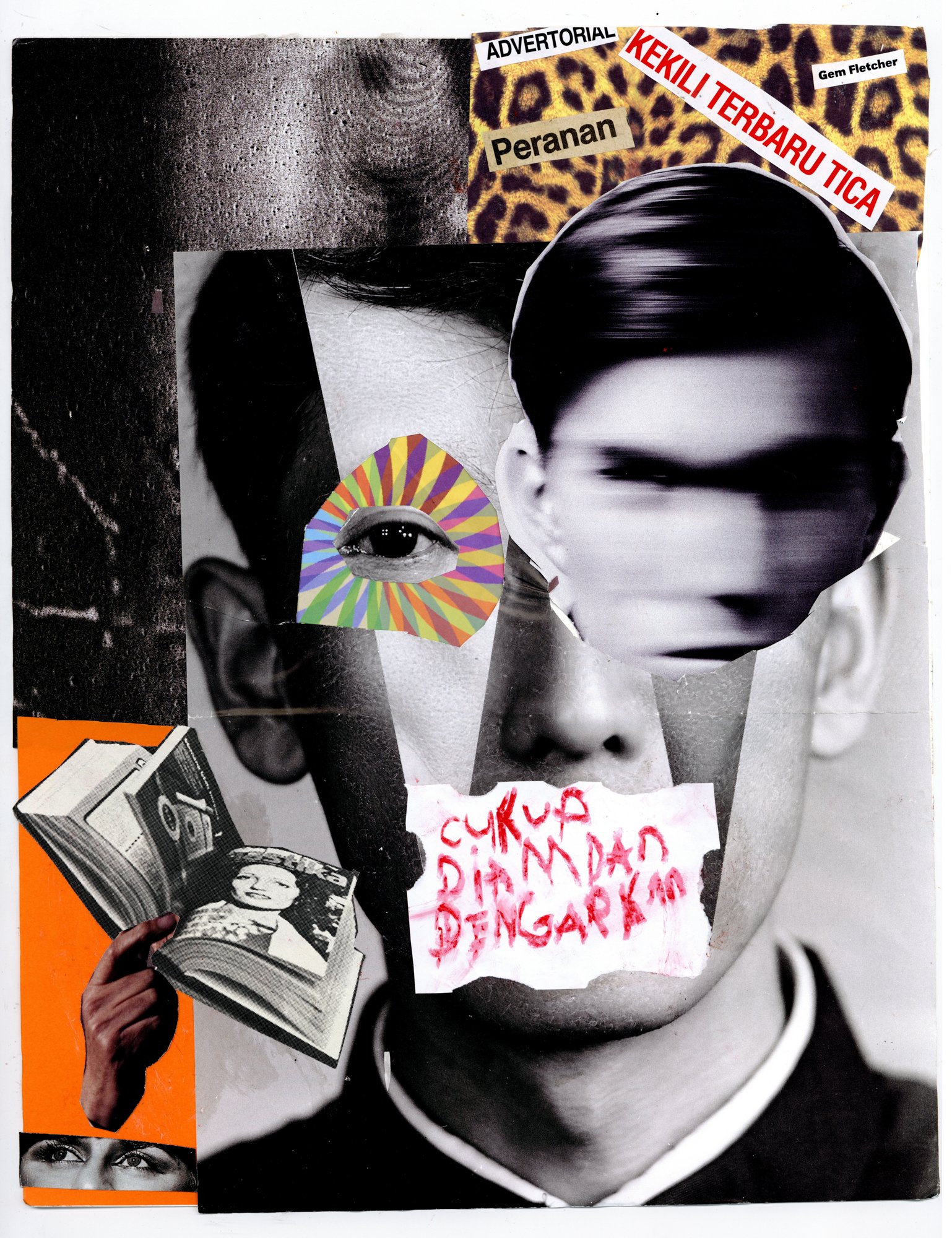

As a result, my approach to this project became collaborative in spirit. As my work there was over a long period, I had to find many different ways to work with the children to maintain stimulation and interest in the classroom. I researched participatory works employed in the realm of photography such as Photovoice practice and looked into works of photographers like Carolyn Drake, Nigel Poor and Wendy Ewald. Consequently, the different approaches resulted in a rather variable visual output that range from conventional photography to collaging. This maintained interest and engagement with the students as it showed them that the methodologies of image-making are not just confined to a camera.

You have been well recognised for your portrait. What is the impact of this on your process? Tell us about your work in the Taylor Wessing Photo Portrait prize.

Right from the very beginning, I’ve always had an affinity towards portrait photography. I always connect better with images that have physical semblance of human representation compared to images that do not. This has definitely influenced how I approached this project, particularly with the youths. As this project was about representation and identity, the usage of portraiture became even more important and meaningful. Whilst their existence is denied by the state, the capturing of their physical form was a symbolic way of acknowledging their own existence, and bestow them a citizenship of sorts, as what Ariella Azouley posits in ‘Civil Contract of Photography’; becoming citizens of images. It is their way of proclaiming and celebrating their own identity.

After over two years of collecting a bank of images, I realise that I was close to the end of the image production stage of my work with the children. Having learnt and seen a lot with them, I felt that I owe it to my students to share our work outside the four walls of the classroom. I wanted to show the world about their lives and their artistic voices. Submission into the Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize was a good prelude to this.

Can you tell us about the process of producing the Zine and what are your hopes for your work?

I wanted to produce something physical and tangible for the students hence, one of the key plans was to produce a collaborative Zine using the images that were made over the past two years of working together.

It was important to me that this Zine had the children’s input because I wanted their personality and identity to shine through apart from showcasing selections of the visual output the collaborative work had produced. I made sure that they were closely involved in the sequencing and design during the production phase. It was an interesting process for me to observe discussion of sequencing in the classroom. It was also eye-opening to them when we discussed about the works of others through photobooks and learn about sequencing from the works of others. It was useful for them to understand that images do not often exist in isolation and forms part of a bigger narrative particularly when the subject matter is complex and broad. In the end, the zine serves as a little window to their lives and the community they belong to.

The production of the Zine was financed by the grant money I received from winning the Taylor Wessing and all the proceeds from the sale will be brought back into the school.

In the future, I will be organising a community-based exhibition in the village where the school is located. I am hopeful that this will serve as a stepping stone to an exhibition in Kuala Lumpur (and outside the country) as I believe that the story of the children should be appreciated and be shared with other Malaysians particularly the pressure groups.